Facing the global spread of COVID-19, comparisons of the numbers of confirmed cases and victims in each country have increased in recent weeks. In particular, reliable sources have published different case-fatality rates for the same country at identical assessment dates.

The case-fatality rate should not be confused with the mortality rate, which is the number of deaths relative to the entire sample under consideration (an area, country, etc.). Indeed, the case-fatality rate corresponds to the number of deaths related, in this case, to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, by the total number of closed cases characterized by two states: recovery and death.

Do not confuse case-fatality

rate with mortality rate.

In this context, the bias in estimating the case-fatality rate is mainly due to the technique of counting the numbers of deaths and infected persons. These counting techniques differ from one country to another, making comparison between them irrelevant in some cases, especially if other factors of divergence are involved. In addition, the estimate of the number of infected persons is subject to controversy due to the fact that the future status of the sick persons (recovery or death) remains unknown at the time of calculation.

For these reasons, the ADDACTIS COVID-19 Task Force has analyzed in details the issues underlying case-fatality rates in order to present the main estimation biases involved in their calculation.

Difficult comparability of reported data

Different screening policies per country

One of the main biases in estimating the case-fatality rate comes from estimating the number of people infected by COVID-19. The latter is directly correlated with the number of screening tests performed, since the more cases are detected, the lower the case-fatality rate.

The more cases are

detected, the lower the

case-fatality rate.

However, different screening policies are being implemented internationally. Some countries, such as South Korea and Germany, have adopted a massive screening strategy for early management of sick people with no or very few symptoms. These countries are among those that have tested their populations the most and have the lowest number of reported deaths. In this context, it should be noted that Iceland leads the world in terms of the number of screening tests carried out to date, per capita.

Other countries, such as France and Switzerland, have preferred to adopt a targeted screening strategy, particularly for people at risk or those with symptoms. Nevertheless, this strategy reduces the estimated number of infected people in the country because of the many asymptomatic cases or people with mild symptoms who will not be identified.

Different counting methods per country

The counting method of COVID-19 deaths also varies from country to country, making comparison of case-fatality rates irrelevant in some cases.

Some countries, such as Spain or Germany, count a death only if the person has already been identified as having COVID-19. This constitutes an undercounting bias in the number of deaths because, as mentioned above, the number of infected persons is currently underestimated.

Other countries report only the number of deaths in hospitals. However, a recent study published in The Guardian showed that more than half of all pandemic deaths occurred in care homes for elderly, dependent persons. This leads to a significant underestimation of the total number of deaths.

Finally, in some countries, the number of deaths at home remains unaccounted for in the official reports of the epidemic, which also constitutes a bias in the estimation of the case-fatality rate. In France, for example, INSEE specifies the share of deaths at home which amounts to 23% from the 1st of March to the 6th of April 2020, without specifying the share of deaths related to COVID-19.

Incubation delays and asymptomatic cases

The incubation period also creates a bias in the estimation of the case-fatality rate: people who were ill and died on a given date were infected earlier. This leads to temporal heterogeneity when taking into account the total number of infected persons at the date of calculation.

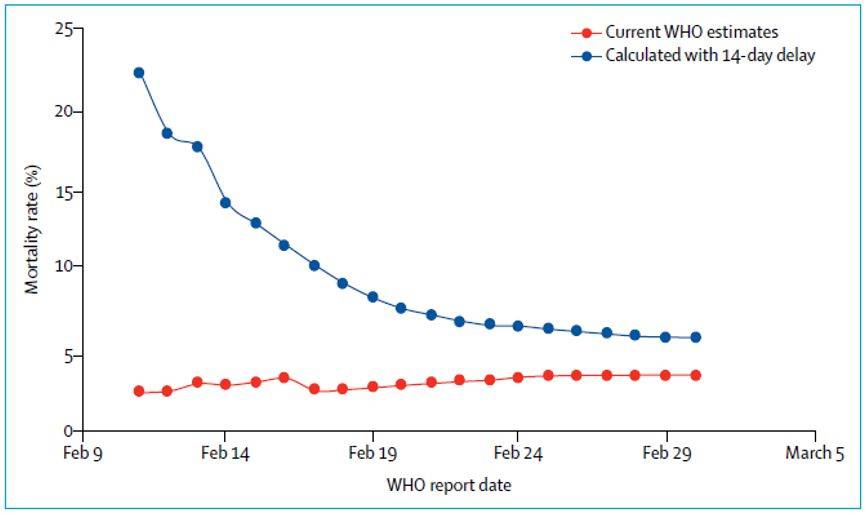

In this context, The Lancet Infectious Diseases highlighted the impact of taking into account the incubation period in the estimation of the case-fatality rate[1]:

Figure 1: Impact of incubation time in estimating case-fatality rate (source: The Lancet Infectious Diseases)

she graph above shows the progress, from February 11 to March 1, 2020, of the WHO global case-fatality rate estimate as at March 1, 2020. Besides, it shows the recalculated case-fatality rate by dividing the total number of deaths by the total number of cases confirmed 14 days beforehand.

It should be remembered that a bias exists, through the construction of the indicators presented, due to the different stage of the epidemic in different countries. Finally, the significant difference observed between the two curves underlines the importance of the quality of the data underlying the calculation of the case-fatality rate.

Non-uniform characteristics and implemented means

Different lockdown strategies in each country

Lockdowns undeniably contribute to reducing the spread of the epidemic due to social distancing. In this context, the majority of European countries have adopted, at different stages, lockdowns. However, the rules vary from one country to another.

Indeed, some countries, such as France and Italy, are applying “strict” lockdown in line with the strategy of slowing down the epidemic spread. Other countries, such as Sweden, do not use lockdown in connection with a “herd immunity” strategy.

Similarly, South Korea, which is characterized by a relatively low case-fatality rate, has not established a lockdown plan. Instead, the country has used its technological resources based on government data collection to identify people in the early stages of the disease (e.g. installation of thermometers in certain locations where cases have been observed, launch of applications requesting the daily health status of the population, etc.).

Finally, the impact of lockdowns is directly observed through the decrease of the number of deaths. This downward effect is intensified when lockdown measures are applied in the early stages of the epidemic.

Variable population characteristics and medical means

The characteristics and lifestyles of a given population have an impact on the evolution of the case-fatality rate. For example, Italy, which has a relatively high case-fatality rate, is characterized, among other things, by a large proportion of elderly people and a fairly strong “extended family” culture with multi-generational living. This accelerated the epidemic spread and increased the number of deaths when young people with strong immune systems introduced the disease to their elderly parents and grandparents. Indeed, the older a population is, the more serious cases there are, leading to a higher number of deaths.

In addition, countries’ medical resources contribute to the recovery of infected people. Indeed, in times of health crisis, excess mortality can result from the saturation of emergency services, particularly with regard to the number of resuscitation and intensive care beds available. Therefore, countries’ efforts regarding medical supplies have increased recently.

Finally, a country’s health care provision also impacts the case-fatality rate. In the United States, for example, millions of people have lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic, including their health insurance policies. Infected persons in this situation are thus unable to pay for high hospitalization costs. As a result, there is a significant upward impact on the number of death.

Case-fatality rate, when will convergence occur?

The actual case-fatality rate of COVID-19 is difficult to quantify. Its estimation will be significantly improved after the crisis. Censorship of available data on infected persons must be taken into account in order to avoid any overestimation of the case-fatality rate.

Moreover, additional discrepancies between scientific publications may be observed due to different methods of mitigating the bias in the case-fatality rate estimate. Indeed, some scientists reprocess the denominator of the case-fatality rate in order to take into account a set of previously mentioned biases, particularly over the incubation period.

Finally, the intrinsic mechanisms to countries’ crisis management strategies have significant impacts on case-fatality rates. Therefore, comparisons within and between countries must be made with caution.

Ines MANAI, Consultant – April 2020

[1] See the detailed study on the website of The Lancet Infectious Diseases.